Soils

Chapter 18

NOTE: We will focus on the Canadian Soil Classification System in this course.

Read the whole chapter. You may SKIM through the details of “Soil Classification,” 4CE pp. 582-599; 3CE pp. 563-583. We will work with this in the lab. (For any Americans in the course, Appendix B, (4CE pp A6-A9; 3CE pp. A6-A9) introduces the classification system used in the USA – you don’t need this information in this course!)

“Listen! A farmer went out to plant some seed.

As he scattered it across his field, some seed fell on a footpath, and the birds came and ate it.

Other seed fell on shallow soil with underlying rock. The plant sprang up quickly, but it soon wilted beneath the hot sun and died because the roots had no nourishment in the shallow soil.

Other seed fell among thorns that shot up and choked out the tender blades so that it produced no grain.

Still other seed fell on fertile soil and produced a crop that was thirty, sixty,

and even a hundred times as much as had been planted …

The farmer I talked about is the one who brings God’s message to others.

The seed that fell on the hard path represents those who hear the message,

but then Satan comes at once and takes it away from them.

The rocky soil represents those who hear the message and receive it with joy.

But like young plants in such soil, their roots don’t go very deep. At first they get along fine,

but they wilt as soon as they have problems or are persecuted because they believe the word.

The thorny ground represents those who hear and accept the Good News,

but all too quickly the message is crowded out by the cares of this life,

the lure of wealth, and the desire for nice things, so no crop is produced.

But the good soil represents those who hear and accept God’s message and produce a huge harvest –

thirty, sixty, or even a hundred times as much as had been planted.”

Mark 4:3-9, 14-20 NLT

**There is a video version of this lecture here: https://youtu.be/meBStS8CXCM

**The exam is based on the content in these notes, so please print them off to study from.

One of the effects of weather and climate, when it interacts with the surface of the earth, is soil. Soil represents rock that has been exposed to the forces of weather and climate over long periods of time, and that has been broken down into smaller particles.

The scientific study of soils is “soil science” or pedology. Scientists who study soils are soil scientists or pedologists.

-

The Nature and Function of Soils

A. What is “soil”?

The atmosphere weathers rocks, through the ongoing effects of water, ice, heat, wind, etc. As this happens, the rocks break down into smaller particles. The original bedrock rock that is weathered into smaller particles is called parent material. The result of parent material or bedrock being broken down through weathering is regolith, a layer of unconsolidated material on the surface of the earth, that is little altered from the parent material except that it is broken up into smaller bits.

Soil is chemically or physically altered parent material. Normally it is formed as organic (plant) material is mixed with the regolith.

Soil is the natural surface layer containing organic matter (living or dead) and supporting (or capable of supporting) plants.

The official Canadian Soil Classification definition of soil is this:

“Soil is defined … as the naturally occurring, unconsolidated, mineral or organic material at least 10 cm thick that occurs at the earth’s surface and is capable of supporting plant growth. … Soil development involves climatic factors and organisms, as conditioned by relief and hence water regime, acting through time on geological materials and thus modifying the properties of the parent material.” (Canada Soil Survey Committee 1978)

Soil, then, is:

- naturally occurring

- unconsolidated material at least 10 cm deep

- contains mineral (rock) and organic (decaying vegetation, microbes, decomposers, etc) material

- occurs at the surface

- can support plant growth

So …

– Solid rock is not soil (not unconsolidated)

– Sand on the beach is not soil (cannot support plant growth)

– A thin smudge of dirt is not soil (not 10 cm thick)

B. Soil as a System

Soil has been viewed as the fundamental component of the abiotic (non-living) part of an ecosystem and exercises significant influence beyond the ecosystem in which it is found:

- soil provides a place for plants to root in

- soil provides a source of water and nutrients for plant life and some animal life (decomposers like worms)

- soil provides habitat for soil micro-organisms involved in decomposition and recycling of nutrients

- outputs from the soil provide nutrients to aquatic ecosystems

- if soil didn’t exist, the entire food chain would cease to exist and all animal life would perish

Soil can be viewed as a subsystem of the whole ecosystem, with inputs from the broader environment, outputs to the environment, and cycling within the system:

-

Inputs and Additions to soil and soil components

a. mineral (inorganic) components from the parent material are the main inputs; normally they are released by weathering at the bottom of the soil profile. The kind of soil that develops in a given location depends on what kind of parent material is there in the first place. Some parent materials weather more readily than others. Soils developed on sandy material will differ from soils developed on heavy clay deposits; the soils of the Great Plains differ from those of the Canadian Shield.

The speed of weathering relates to:

– how resistant the bedrock is

granite is very resistant and weathers slowly;

sandstone/limestone are less resistant and weather more quickly,

– climate

warm moist climate = much weathering (e.g. in tropical areas, and west coast of Canada);

cold, dry climate = little weathering (e.g. Arctic and prairie areas).

Where little weathering occurs, soils will be thin and poorly developed. With much weathering, soils will be deep and well developed. In Canada, parent material derives from weathering of bedrock, but also from

- glacial deposits (from ice ages) also called morainal deposits (moraines are the piles of sediment associated with glaciers),

- lacustrine (lake), fluvial (river) and marine (ocean) deposits in regions where large bodies of water (lakes, rivers, or oceans) appeared to have once been, or in regions where flooding occurs

- eolian deposits (from wind blown sediment).

b. organic material from plants (in the form of leaves, plant litter and dead roots) is important since it attracts decomposers that convert the organic forms of elements into mineral material that can be taken up by plants. The amount of organic input is related to the density of vegetation (which is often a direct function of climate). Thus warm moist areas support much vegetation and thus have a high organic component within their soils. The opposite is true in cold, dry areas.

c. inflow of groundwater, carrying minerals and nutrients from outside the region.

2. Outputs and Removals of soil and soil components:

a. erosion is the removal of weathered material by water, wind or ice. It results in soil being physically removed from a region. The amount of soil erosion is a function of many factors including climate, soil conditions, vegetation cover, topography and disturbance.

b. leaching is the loss of dissolved soil materials (especially minerals which serve as plant nutrients). The entire soil is not physically removed (as in erosion), but specific minerals/nutrients are dissolved in water and washed out of the soil. This is very important in regions with high precipitation, rapid drainage, and acidic plant cover (i.e. the west coast)

II. Soil Profiles

1. Pedons and horizons

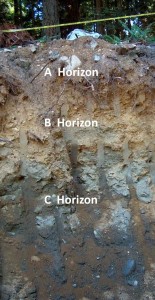

Soils are not uniform as you dig down. If you were to dig a hole, you may notice that the top layer is dark brown or black. Lower is a lighter, brownish layer. Still lower you may hit clay. Soil scientists (pedologists) usually study soils by looking at vertical cross-sections, or profiles, of soils. This is also called a pedon (See Figure 18.2, “A typical soil… (4CE) p. 573, (fig. 18.1, “Soil sampling and mapping units” and fig. 18.2, “A typical soil profile,” 3CE pp. 557)).

Several pedons together, all having the same characteristics, are called a polypedon. Pedologists have produced soil maps for all of Canada and the U.S. showing the dominant soil types (polypedons) in various areas.

Within a pedon or soil profile, the various horizontal layers are called soil horizons. Each horizon may have distinctive colour, texture, mineral and organic content. There are typically four distinct layers in most soils:

– O (organic), L (Litter) or LF (Litter, Fermenting/rotting) or LFH (Litter, Fermenting/rotting, Humus) horizon – decaying organic matter (fallen leaves, twigs, etc.) on top of the soil.

– A horizon (top layer) – regolith substantially altered by organic and other material from the surface

– B horizon (middle layer) – regolith mixed with some organic and other material from the surface

– C horizon (deepest) – regolith: virtually identical in mineral content to the original parent material. Unaltered chemically.

B. Composition of horizons

Soil is composed of three basic components:

- organic and inorganic mineral particles

- water (in at least one of its 3 states). Soil water is generally enriched by dissolved elements such as Ca (calcium), N (nitrogen), Fe (iron), etc.

- air which is somewhat different from free air in the atmosphere, due to diffusion from the soil and respiration of soil biota

These will vary depending upon the layer or horizon within the soil:

-

Composition

Composition of the soil – in terms of its mineral material, organic content, water, and air – changes with depth.

A horizons: Topsoil (A-horizons) contains a high proportion of components from the surface – air and organic matter

B horizons: Subsoil (B-horizon) contains proportionately less air and organic matter.

C horizons: Unconsolidated parent material (regolith or C-horizon) contains very little air or organic material. Bedrock, of course, contains no air or organic material.

Water is derived both from the surface (precipitation) and from groundwater flow (and is stored as groundwater) so, depending on the physical properties of the soil, all layers can contain substantial amounts of water.

2. Colour

Colour varies with depth as the composition changes – usually the colours are indicative of compositional changes:

In general, soil layers with high proportions of organic material (A-horizons) are darker than layers primarily composed of parent material (commonly light-coloured quartz, feldspar and clay minerals)

Colour depends upon the presence of minerals with distinctive appearances (such as iron)

Colour also varies with precipitation; the higher the rainfall, the more organic material is “washed through” and the less distinctively dark an A-horizon develops;

e.g. Prairie (chernozem) soils have a black humus-rich A-horizon; west and east coast (podzol) soils, where much of this organic material has washed through, do not

-

Processes of reorganization within the soil

downward translocation

The character of a soil profile also depends upon several processes that may be involved in the reorganisation of minerals or materials within the soil. Notice that many of these processes are closely related to weather and climate. Leaching (b), for instance, is only a major factor in warm, wet climates. Upward translocation (c), however, is only a factor in warm, dry climates. Read on …

1. clay translocation (or eluviation) is the physical transport of clay particles by percolating rain water that passes down root channels, interconnected pore spaces, worm holes, etc. This process results in a C horizon that has a very high clay content. Fine clay particles have been washed down and form a thick layer. When you dig down and “hit” clay, it is very difficult to dig any further. The clay creates a solid layer. This is common on both east and west coasts.

2. leaching occurs when rain water picks up CO2 and other minerals. These chemicals make the water slightly to strongly acidic. This acidic water dissolves and combines with mineral material in the soil profile and washes it down. The result is a soil that is quite acidic. And a soil where many of the nutrients plants need (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) have been washed out. This process removes the more soluble elements from the surface layers of the soil, leaving the topsoil acidic and relatively infertile. Leaching is more pronounced:

– under vegetation that promotes acidic surface litter (e.g. coniferous/evergreen trees), and

– in locations with high precipitation or excessive irrigation/watering.

Salt has formed a crust on this soil as soil moisture has been evaporated, near Granum, AB

This process has a significant effect on fertilizer since the nutrients in fertilizers can be washed into lower soil horizons. This removes nutrients from where you want them (near the surface) and concentrates them in the lower horizons.

Note the most commercial fertilizers for domestic use have 3 numbers (e.g. 20-30-10). These represent the three most common nutrients leached from soils – N, P, K – Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P), and Potassium (K). For example, a 20-30-10 fertilizer would contain 20% by weight of nitrogen, 30% by weight of a phosphorus compound, and 10% by weight of a potassium compouond. The other 40% would be some inert (non-chemically active) ingredient. By convention, the three numbers on a fertilizer are always in the order N-P-K (know this – it may actually be useful some day!)

3. upward translocation occurs in dry lands, where evaporation removes water from the surface of the soil. As water near the surface evaporates, water from deeper down is drawn to the surface by capillary action. This water often contains high levels of dissolved minerals, particularly salt. As this new water is evaporated, the dissolved salts are left behind. The result is a layer of white salt at the surface. This process moves salt from deep in the soil to the surface. The result is a soil with a hard white crust at the top (right).

4. biological processes include ways in which plants draw minerals (often from great depths) to the surface through their roots, and ways in which plants deposit organic litter on the surface. The net effect is the minerals are moved from deep in the soil to the surface.

5. physical mixing occurs when soil is mixed through physical processes including:

- small animals

- root growth and uprooting of trees,

- ice crystals causes surface mixing within a shallow layer

- seasonal freezing causes mechanical mixing and churning of the soil; this is particularly effective in permafrost-affected soils (cryoturbation)

- ploughing, excavation and other human activities

6. gleying occurs in soil that is saturated for periods of time. The chemical processes result of oxidation and reduction chemically change metal minerals (iron, aluminum) in the soil. Gleyed horizons tend to be dominated by grey or green colours when saturated, but these colours change to reds and yellows when dried. In essence the metal minerals in the soil “rust.” Since wetting and drying can occur seasonally mottling can result where pockets of soil of various colours can be found.

III. Soil formation and soil properties:

As parent material is broken down or altered, and as other materials are inputed or outputed, distinctive soil types with distinctive profiles develop. Properties of these soils are used to aid in classifying (or naming) soil types. These properties include:

A. Soil texture

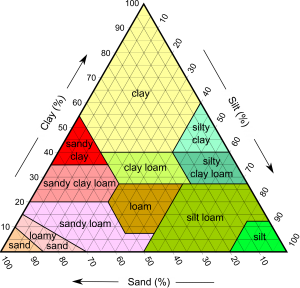

Soil may be graded according to the size of the particles, the soil texture. From large to small, particles are classified as:

- stones (over 25 cm in diameter),

- cobbles (7.5 cm – 25 cm)

- gravel (2.0 mm – 7.5 cm)

- sand (0.05 mm – 2.0 mm),

- silt (0.002 mm – 0.05 mm)

- and clay (less than 0.002 mm)

The most important of these are sand, silt and clay because they hold water and nutrients in the soil and are affected by the processes of translocation, leaching, gleying, etc. These, collectively called the fine earth fraction of the soil, are the critical components for soil fertility and water retention.

- Soil with a high percentage of sand holds little water, falls apart easily, and can hold few nutrients.

- Soil with a high percentage of silt holds some water, holds together somewhat, and can hold some nutrients.

- Soil with a high percentage of clay holds much water, holds together very well, and can hold many nutrients.

Soil texture depends upon the character of the original parent material (what types of particles are produced by weathering). It also depends upon the intensity of weathering (heat and moisture), and time. More intense and longer duration weathering will result in higher proportions of small clay particles.

Soil texture is described on the basis of the relative proportions of sand, silt and clay. When soil is described sy SOIL TEXTURE, the percentages are ALWAYS given in the order of % sand, % silt, and % clay. So, a soil with a texture of 20/50/30 is 20% sand, 50% silt, and 30% clay.

Remember that

- A high clay percentage will result in poor drainage, but good nutrient retention.

- A low clay percentage will result in good drainage but no nutrient retention

- A moderate clay percentage will result in adequate drainage and nutrient retention – best! The most fertile soils have a moderate amount of clay. The most fertile soils of all have a balance of sand, silt, and clay.

See Figure 18.4, “Soil texture triangle,” 4CE p. 575; 3CE p. 559. You will use this figure in your lab this week.

What you need to remember is the numbers are always in the order: sand, silt, clay (drill it in to tour memory: sand, silt, clay … sand, silt, clay… sand, silt, clay ..)

So if your sample is 20/70/10

So, start with sand. In this example, the % sand is 20. So, go along the bottom from right to left to 20. Your sample will be along that 20 “line” somewhere.

Next go to silt — 70%. Silt is along the right hand side. Go down from the top to 70. When you find 70 on the silt axis (edge), your sample will be along that line.

Last, go to clay — 10%. Clay is along the left side. Go to 10. Clay is the easiest because the white lines go horizontally, so you go across on the 10 line.

And you’re there! A beautiful SILT LOAM!

It is a bit confusing! The key is to remember it’s always SAND-SILT-CLAY! And to make sure you are using the correct side.

B. Clay Content

Clay is the most important inorganic component of soil:

(a) it tends to act as the “glue” that holds soil together,

(b) it holds water in the soil,

(c) it stores nutrients for plants.

Clay particles are very small, thus they have a large surface area to volume ratio, providing lots of area for water to adhere to. Some clay particles are also structured so they can actually absorb water like a sponge; they swell when wet and shrink when dry. (see an example)

- Soils rich in clay will tend to hold much water and drain relatively poorly.

- In contrast, soils with high proportions of larger particles (sand and bigger) will drain well and hold little moisture.

Clay particles also have a net negative electrical charge (they are called anions – negatively charged particles) enabling them to attract and hold positively charged ions. Opposites attract! Most nutrients that plants like have a positive charge they are called cations – positively [or puss-itively] charged particles). Thus clay is essential to healthy plants! It attracts and holds positively charged nutrients that plants may then take up through their roots.

Clay can be described in terms of its cation exchange capacity – how many positively charged particles it can hold. The presence of clay with a high cation exchange capacity within a soil will give it a high fertility – it can grow lots of plants because it can fold lots of nutrients!

C. Soil Structure

Soil is rarely a collection of loose grains. It clumps together. The clay and organic components within the soil create this cohesion.

The electrical polarity of clay particles that attracts and holds positively charged ions also acts as “bridges” between soil particles to aggregates, or clumps of soil. Thus soils with high clay contents will tend to “stick together” well. (Think of that clay “gumbo” you get on your boots in springtime!) Soil with high sand content will not stick together well (you don’t get the same “gumbo” on a sandy beach!).

Organic matter, when it decomposes, also tends to hold soil particles together. Earthworms are among the most important decomposers of organic materials; thus the healthiest soils are those with healthy worm populations.

D. Soil pH

The pH of soil is one of the prime determinants of its fertility (how well it grows things).

Remember a pH of 0-7 is acidic; 7-14 is alkaline (or basic).

Remember also that pH is a logarithmic scale: 3 is 10X as acidic as 4, and a 3 is 100X as acidic as 5!

Optimum plant growth happens with a soil pH between 6 – 7. In acidic soils (below 6), nutrients are easily leached out and not available for pants to access. In alkaline soils (above 7), nutrients are insoluble and plants cannot access them.

E. Calcium carbonate content

Calcium carbonate is one of the main chemicals that is easily removed by leaching. Thus it is not present in acidic (low pH) soils that have been heavily leached. Calcium carbonate is critical to soil structure, however, because it acts as cement to bind clay particles together. Thus in soils with low pH, calcium carbonate (in the form of lime) is often added, to compensate for leaching.

F. Organic matter (OM) content

OM is deposited at the surface as plant and animal organisms die. In its initial state it is called a litter layer (L). As it begins to decompose it is called a fermentation layer (F), en route to total decomposition called humus (H). Soils often have a layer, on top of the A horizon, that is composed of one or all of these layers of organic mater. So soils may have an L, LF, or LFH layer on top of the A horizon.

- With cool temperatures and wet or acidic soils decomposition is slow.

- Decomposition happens most quickly in very warm regions with moderate water content.

Where worms and other organisms mix the humus with soil, the humus becomes bonded with mineral particles and acts as a cementing agent, stabilising soil structure.

OM quantity and characteristics are determined by the type and nature of the vegetation producing the litter – acidic litter under evergreens produces acid organic content which promotes leaching. Litter under grasses is richer in calcium and promotes a more balanced pH soil environment.

IV. Soil Description and Classification

The combination of global climate regions (including weather and climate) and global geologic regions (that is responsible for the parent material) results in the presence of dominant soil types in regions throughout the world. Because each country has unique climate and geologic conditions, different countries have developed unique soil classification systems.

SKIM through the details of “Soil Classification,” 4CE pp. 582-599; 3CE pp. 563-583. We will work with this in the lab. The full Canadian System of Soil Classification is here. (For any Americans in the course, Appendix B, 4CE pp. A6- A9; 3CE pp. A6-A9 introduces the classification system used in the USA – interesting, but you don’t need to know it for this course. Other countries have their own classification systems).

In Canada we use a system modified from an approach to soil classification originally developed by Russian scientists early in this century (thus, the “names” are Russian). Canada’s climate and geology are relatively similar to Russia’s, so this makes logical sense!

How the Canadian System Works

The Canadian System of Soil Classification (CSSC) describes soils in terms of the characteristics of each horizon (A, B, C) and the layers of organic material at the surface (L, F, H).

Lower case letters are used to identify key characteristics of each horizon (a horizon may be described by one or two of these) Simply:

- e – a horizon characterised by translocation (or eluviation – downward movement) of clay, iron, aluminum or organic matter

- f – indicates presence of iron (Fe), aluminum and organic matter

- g – gleyed horizon, grey or mottled because of periodic saturation

- h – a horizon enriched with organic matter (humus), usually dark in colour

- m – a horizon slightly affected by chemical processes including hydrolysis, oxidation or solution

- s/sa – horizons rich in salts

- t – a horizon rich in clay

Thus an Ah horizon means the top layer (A horizon) of the soil is rich in humus.

An Ahe would be similar, but some translocation, or downward particle movement, because of precipitation.

An Ae horizon would have had much of the humus, clay and other minerals washed out of it into lower horizons.

-

Soil Orders

The combination of these various horizons creates distinctive soil orders, or types, which are then named.

4CE: see pp. 583-596; 3CE: see pp. 565-573

In this week’s lab you will be introduced to how this system works in more detail.

Canadian Soil Information Service has an excellent website with maps and resources on Canadian soils and soil classification:

- The Canadian System of Soil Classification Manual (3rd Ed) is available on line

- There are folders on each of major Canadian soil orders

- There are maps of soil orders in Canada

Most provincial departments of agriculture have lots of information on soils, including

- BC Soils

- Alberta Soil Information Centre

- Soils of Saskatchewan – Home

- The Soil Landscapes of Manitoba

- Ontario Soils

- Soil surveys for Quebec

- New Brunswick

- Prince Edward Island Information: Provincial Soil

- Newfoundland/Labrador Soils

In contrast to a province like Alberta or Ontario with several soil types, a smaller province, like New Brunswick (and actually most of the Atlantic provinces), is dominantly one soil type: podzolic (see Figure 18.11; 4CE, p. 585 (Figure 18.9, 3CE p. 567). The parent material of the soil is a moderately compact glacial till.

Know these basic soils:

Chernozems: dark, rich prairie soils (lots of vegetation, little moisture to cause leaching) – very fertile.

A podzol soil, Keats Island, BC

Podzols: light, leached soils typical of the west coast, northern Ontario and Quebec, and the Atlantic region (lots of acidic – coniferous – vegetation, lots of moisture and lots of leaching) – not too fertile.

Luvisols: moderately dark, fine grained soils in southern Ontario and northern Alberta. Clay is leached out of top layers and accumulated lower down – often quite fertile.

Organic soils – basically bog, peat soils in perennially water saturated areas.

Cryosols (US axonomy “gelisol”)– Arctic soils, in regions with much permafrost. Poorly developed.

Gleysols – high clay content soils, strongly influence by gleying (see above).

Worth Reflecting On …

- “Does Christianity Hinder Science?” – a short video with a molecular biologist, Adrian

- “Dr Ruth Bancewicz: Science & Wonder,” a longer video, but an excellent, thought-provoking talk (you don’t have to watch it, but I really recommend it … and she has a great Scottish accent. 🙂

- Gerard Manley Hopkins writes:

| God’s Grandeur |

|

What are your thoughts on the themes Hopkins brings up? About human use/abuse of creation? About the sustaining power of the Holy Spirit (Holy Ghost)? Feel free to discuss this quote on the course discussion site

To review …

Check out the resources at www.masteringgeography.com

This page is the intellectual property of the author, Bruce Martin, and is copyrighted © by Bruce Martin. This page may be copied or printed only for educational purposes by students registered in courses taught by Dr. Bruce Martin. Any other use constitutes a criminal offence.

Scripture quotations marked (NLT) are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Wheaton, Illinois 60189. All rights reserved